I haven’t had much time for new research this month, so I thought I’d go through some heraldic registrations I’ve done in recent years.

The Company of the Dawne

The device for the Company had already been designed, and the name in widespread use during the Covid years, but it required registration, which is a little more tricky. The initial thought would be to name it after one of the private mercenary companies that operated in Europe during our period, especially within Italy. One of the more famous of these is ‘The White Company of the Hawk’ (Compagnia Bianca del Falco), led by the Englishman John Hawkwood. This was also known as the ‘The English Company’, and earlier ‘The Great Company of English and Germans’ under its first commander, Albert Sterz.

The problem is that these patterns don’t match the use of a concept like The Dawn Company. You certainly don’t find words like dawn used in the same ways as adjectives such as white. In modern English, however, you might translate something on the lines of ‘The Company of the Dawn’ as ‘The Dawn Company’. So let’s try that.

Dawn in Italian translates to Alba, so we’d be looking for a name like ‘Compagnia dell’ Alba’. Alba is the name of a town, and a surname (although my knowledge of Italian records wasn’t good enough to document it to period). However, in both cases you would have ‘The Company of Alba’ (‘Compagnia di Alba’), rather than using the nickname of ‘the Dawn’, analogous to the ‘the Hawk’. So we leave my limited abilities in Italian.

In an English context, what about private military companies? As far as I could see they were all named for people, so again not ‘of the’, and nothing based on more nebulous concepts such as the dawn. Names in period tend to be associated with definitive places or people, rather than generic concepts, which is far more common in modern naming. There are exceptions, usually associated with religious virtues, or otherwise with heraldic imagery, but heraldry is limited to identifiable things.

However, there is one way to get to a ‘Company of the’ in English, and that is with the crews of ships, using its name. This pattern is evident in documents such as HCA 30/840/30, from 1636, in the UK National Archives: “John Holt, Andrew Davys, Edward Burges, Briant Middleton, Thomas Smyth, Edward Dale, James Lucy, Thomas Shotten, Edmond Weekes, Emanuel Rogers, Josias Wilkinson, James Symes, John Clarke, Roger Russell, John Jones, Phillip Pritchards, Thomas Ayres and Constantine Woodroff, company of the White Lion of which Thomas Middleton was the master”. It’s also a pattern that the College of Heralds recognizes for registration. So we have the pattern, and the problem changes to documenting a ship called the Dawn.

To this end, I went through a number of the SC8 records ay the UK National Archives, as well as some other directly transcribed catalogue entries. The SC8 series have the advantage of being freely available as digital images, so you can see what is actually written, albeit often in Norman French. The extracted names can be found here. (which is based on just a sample, and hence far from comprehensive). This shows the development of the three main patterns: saints, places and people, the latter as full, first or surnames. But no concepts in the way we would think of them.

The most promising avenue, would be personal names. It’s probably rarer not to be able to document something in the English naming pool than to be able to. For example, Darth Vader is a plausible English name using period naming patterns, although, to my knowledge, no actual individual ever bore it.

Examples of such ships include:

- the barke berrye

- the Buysse of Briele

- the Godeyere of Newcastle

- the Minnikin / the Mynykyn

Dawn is a modern first name, but I couldn’t document that to period. I was also somewhat surprised to only find Dawn as a surname a couple of times. However, the variant Dawne was far more common. I usually use parish records as my first stop for finding names; they are after all intended to be lists of every person who was born (given baptism was ubiquitous), married and died (given that burial was essential), and for those interested in the details:

- Wootton Wawen, Warwickshire: Marriage 1646 Julij: 26 Rob[er]tus Salt & Johanna dawne

- Shustoke, Warwickshire: 1563: John dawne the sonne of Johne dawne was baptized ye xxv day of Aprell

- Tamworth, Staffordshire: October 1566: 17 were M[arried]: Andrew Cowp & Ales Dawne.

- Brandesburton, Yorkshire: Marriage: 1578: Novembris 23: Gilbertus Dawne & Isabella Rarnar

- Tenterden, Kent: January 1580: Josephe Dawne bur[ie]d y 18th of Janua[ry]

Hence, using a ship named for someone in the Dawne family, we end up with the registered name of ‘The Company of the Dawne’.

This doesn’t reflect the actual purpose of Insulae Draconis’s Dawn Company, but does reflect a common SCA practice of a new guild, institution or group being named first and registered later. Unfortunately, many of the naming patterns that tend to be imagined as period in sound and construction tend to actually originate in the pages of fantasy novels, rather than in medieval practice. This leads to quite a lot of registrations in which established names have to be retrospectively engineered to fit a period pattern, in order that they can pass College of Heralds standards.

This isn’t arbitrary, but a reflection of those researching names wanting to apply the same standards of period practice as any of those who research, for example, cloth, clothes or cooking, and much as a cook would encourage you to use and adapt period recipes, I encourage you to check period naming patterns before the fact.

The Armourers Guild

I was consulted on the name and armoury of this new guild at its inception, which meant I was able to follow period patterns from the start. From a College of Heralds point of view, this guild was generic enough that it didn’t need a name registration, and any arms could be registered to the Armourer’s Guild of Drachenwald.

Having said that, however, the guild still needed a decent name for its charter. In actual fact, I had difficulty in tracking down many examples of such guilds across Europe, which may just reflect the esoteric nature of the search and perhaps a lack of online translations. However, being English myself, as was the founder, the most obvious example to follow was that of the guild in the City of London. This still exists, now combined with the Brazier’s Guild, a merger which happened in 1707, and pops up as a sponsor of events at the Materials Science Department of Cambridge University from time to time. The Armourers Guild of the City of London was founded in 1322, and received a Royal Charter in 1453, which refers to the Brothers and Sisters of the Fraternity or Guild of St. George, of the Mystery of the Armourers of the City of London.

I retained the essential pattern, but made some of the terminology more neutral, whilst using period wording, and replaced the English patron saint of St. George, with Albion, who in many ways occupies the same position for Drachenwald. Thus, it became The fellowship of the guild of Albion of the Mystery of the Armourers of the Kingdom of Drachenwald.

Next came the business of registering the guild arms. In SCA terms, this had to be a badge registered to Drachenwald, as the SCA has the slightly odd notion that people and groups can only register one device, but numerous badges. I’ll forego my usual exposition on this approach.

In looking to follow period inspiration, there was obviously the London guild arms. I tried to find some other European examples, but the only one I could turn up was the Florentine ‘Arte dei Corazzai e Spadai’

The combined arms of the Armourers and Braziers Guild of the City of London (modern rendition in colour)

The armes of all the cheife corporatons [sic] of England, 1596 English (LUNA: Folger Digital Image Collection, STC 26018)

Arte dei Corazzai e Spadai’ (modern rendition)

It’s worth noting in passing that the London guild’s arms exceed the SCA general limit for complexity, and provides a period example for documenting an exception. With 7 charges (chief, chevron, swords, gauntlet, helms, roundel and cross) and 4 colours (Or, argent, sable and gules), it comes in with a complexity count of 11, with the default limit being 8.

I took both as examples for possible arms, and myself and the founder decided upon the London derived example, perhaps biased as we’re both culturally English. Like the name, the emblem of St. George was replaced with Albion. However, one of the key features of Albion, is that they are black., which wouldn’t work on the black chief. As such, I decided to move the charges off the chief on to the field itself, which also required the helms to become a colour. Following the style and palette of the original, they also became black. It wasn’t the motivation, but this change also has the effect of reducing the complexity as measured in SCA terms, by removing the chief, roundel and cross, and the tincture gules, although adding a dragon, giving a new count of 8.

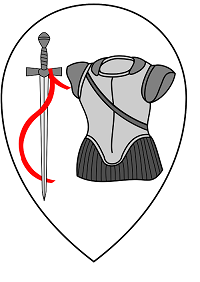

Registered device (as a badge) of the Armourers Guild of Drachenwald.

Whilst the registered example uses great helms, the submission explicitly requested they be blazoned as just helms. This allows people to adapt the helms to their personas’ place and time as an artistic detail, although there’s no getting away from the fact that the overall design will remain late period, English guild style.

For those interested in the minutiae of the SCA heraldic rules, there are a couple of potential problems with the device, although they would in practice be negated by the fact that it is based on a period example, and such examples will always trup existing rules. The first is often referred to as the Unity of Orientation rule, wherein charges must be aligned together. However, the decision directly addressed this, stating “This badge does not have a Unity of Orientation issue under SENA A2D2c; that section explicitly only applies to charges that have comparable orientations, which swords (long charges) and gauntlets (compact orientable charges) do not.”

The second issue comes down to the statement that ‘A single charge group may only have one tertiary charge group on it.’, the assertion being that the swords and gauny gauntlet could not be described together as a single group. It’s a shame the decision didn’t comment on this. However, one commenter had a look for the patterns of two charge groups in the 1550-1555 Insignia Anglica [BSB Cod.icon. 291], which doesn’t actually include the livery companies, and found examples of the form:

‘an A between two B’ (pretty common) ‘in cross an A between four B’ ‘in saltire an A between four B’

So, whilst under the current rules, tertiary charge groups (charges on charges) nominally have to be a single charge group, it is clear that what might be called simple tertiary charge group patterns also existed, at least in late-period heraldry, and hence can be used in submissions, although you would currently need to send in supporting documentation.