As some of you will know I enjoy genealogy. There’s a lot of rubbish online, where one tree blindly copies some poor or deliberately falsified research aimed at getting people to famous or gateway ancestors. Much of this was done before the internet made it easy to falsify, but also easy to disseminate. However, the internet has also made it relatively easy to do proper research yourself. To do it properly, ie. looking at copies of the original records rather than poor indexes, isn’t free, but it is certainly cheaper tha it used to be in money and time than having to personally visit the county archives, and in even older times, the individual parish churches.

The Genetic Caveat

Whilst as a member of the SCA it’s cool to link yourself back to the the period we cover, and perhaps to specific people, some of whom may be famous or infamous, it is worth bearing in mind that despite a direct lineage, the likelihood of a significant share of your DNA coming from that person is tiny, naively in the region of the eighth decimal place after 25 generations. I did initially write more detail as to the factors that govern this but it rapidly became too mathematical for the intent of this article. If people ask, I can do a follow up article. The only DNA, barring mutations, that will be shared in toto, are your mitochondria with your maternal line, which given the gender bias in history, is the hardest to trace, and if you are phenotypically male, the non-homogenous section of your Y-chromosome with your paternal line (barring developmental edge cases). You see, even that sentence got complicated quickly. And all that doesn’t take into account hidden assignations which will break the genetic link, if not the social one.

The Fun Bit

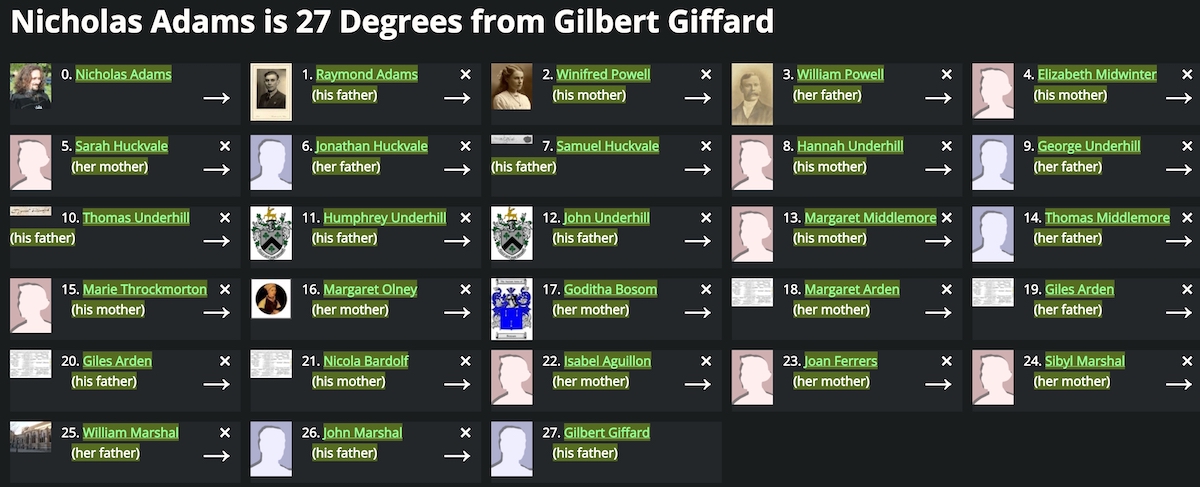

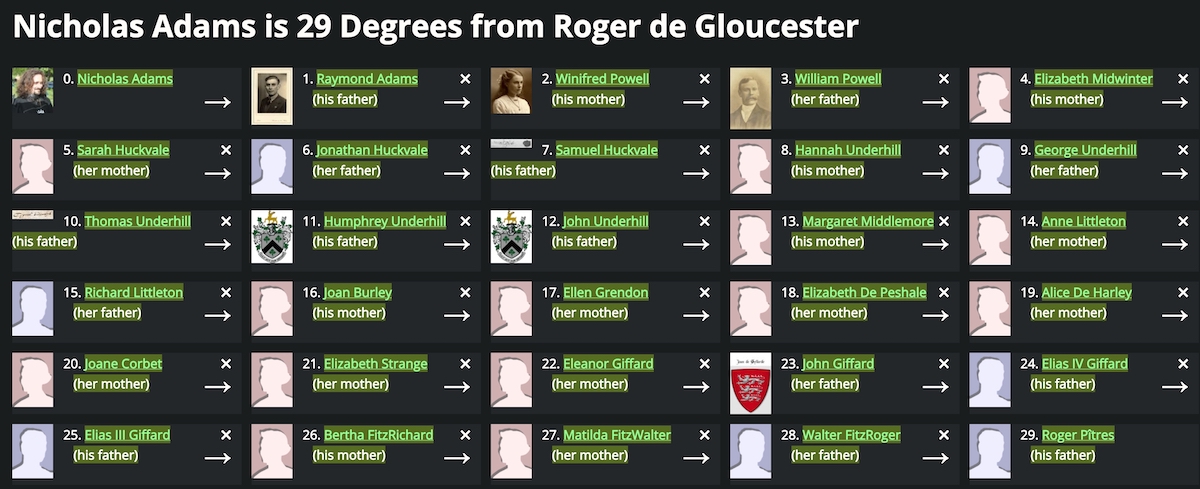

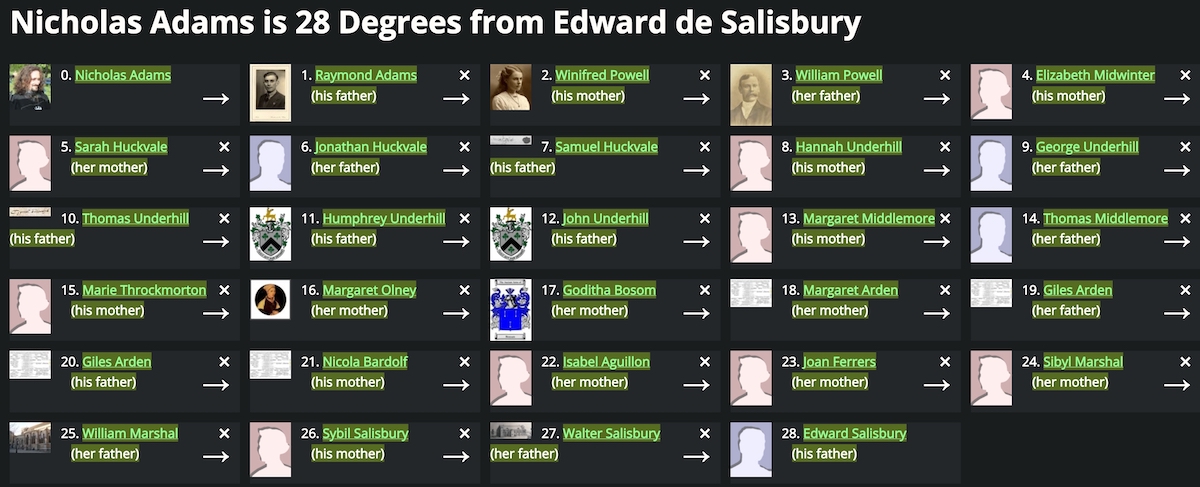

I’ve used WikiTree to generate the diagrams below: they’re an easy way to see the lineages. The fun bit for myself is to use myself as one end of those lineages.

I’ve chosen a couple of targets. The first is William Marshall, sometimes referred to as the Greatest Knight, who served successive kings during the period of Henry II and his brood, rising from a lower son with few prospects beyond his knighthood and serving a lord, to the Earl of Pembroke and finally Regent of England. Rather pleasingly he seems to be my 23 rd great-grandfather through his daughter Sibyl. The paternal line can be taken back a couple more paternal generations.

The second is for connections to the holders of Coldicot Castle in Monmouthshire. Here there are two connections. The first is Walter fitzRoger, my 26th great-grandfather, in the late 11th and early 12th centuries. His son Miles had no surviving male heirs and the estate and castle passed to the de Bohun family through the marriage of his daughter, Margaret, to Humphrey de Bohun. It appears I have no known direct ancestry to their holders of the castle. But turns out Humphrey’s grandfather, Edward de Salisbury, is also my 26th great- grandfather.

These connections also illustrate the interconnectedness of the powerful families. It turns out that my lineage to Edward is also via William Marshal, this time through William’s mother. Beyond that, these two lines have a common ancestor to the third in Margaret Middlemore, who married into the Underhill family, who lived in the first half of the 16th century.

The Weighted Wheel

Of course, most of us could trace some line or other into these families. Our ancestors had the concept of the wheel of fate moving you up and down the social ladder. The reality is that in societies with primogeniture wealth and status stays locked into a very small top tier, where turnover is low. For those in these families, where primogeniture was all, is that unless you were the 1st born male, or inherited in place of one, your most likely social trajectory was down, a bit further with each succeeding non-primary male, and most sisters, drifting ever further from the top tier. That rapidly reaches the richer commoners, such as merchants; who may be on their way up, but whose descendants end up in the same rut, even if the children do manage to marry into old money. The drift can go all the way down to the labourers at the bottom of the pile.