Lactose intolerance afflicts a great many people, some estimates are as high as one in ten. Her Highness Princess Euphrosyne of Insulae Draconis is one of them, which gave me the idea of making some lactose-free cheese. I make cheese pretty regularly for our household, but have not tried to make a lactose-free version before. A little research suggests that the process is essentially unchanged, one simply begins with lactose-free milk. Since I have a brand-new cheese press, and could acquire lactose-free milk, the game was afoot.

We don’t have a lot of information on period cheese-making, but the recipes we do have, including some from Digby and Markham, which are only slightly post-period, show that the basic process is unchanged. Markham writes:

To make a new milk cheese compound.

To make a new milk or morning milk cheese, which is the best cheese made ordinarily in our kingdom; you shall take your milk early in the morning as it comes from the cow, and sile it into a cleane tub, then take all the cream also from the milk you milked the evening before, and strain it into your new milk: then take a pretty quantity of clean water, and having made it scalding hot, poure it into the milk also to scald the cream and it together, then let it stand, and cool it with a dish til it be no more then lukewarm; then go to the pot where your earning bags hangs, and draw from thence so much of the earning without stirring of the bag, as will serve for your proportion of milk, and strain it therein very carefully; for if the least mote of the curd of the earning fall into the cheese, it will make the cheese rot and mould; when your earnings is put in you shall cover the milk, and so let it stand half an hour or thereabouts; for if the earning be good it will come in that space; but if you see it doth not, then you shall put in more: being come, you shall with a dish in your hand break and mash the curd together, possing and turning it about diversly: which done, with the flat palms of your hands very gently pressethe curde down into the bottom of the tub, then with a thin dish take the whey from it as clean as you can, and so having prepared your cheese-vat answerable to the proportion of your curd with both your hands joined together, put your curd therein and break it and pres it down hard into the vat till you have filled it; then lay upon the top of the curd your flat cheese board, and a little small weight thereupon, that the whey may drop from it into the under vessell; when it hath done dropping, take a large cheese cloth, and having wet it in the cold water, lay it on the cheese board, and then turn the cheese upon it; then lay the cloth into the cheese-vat: and so put the cheese therein again, and with a thin slice thrust the same down close on every side: then laying the cloth also over the top to lay on the cheese board, and so carry it to your great press, and there press it under a sufficient waight: after it hath been there pressed half an hour, you shall take it and turn it into a dry cloth, and put it into the press again, and thus you shall turn it into dry cloths at least five or six times in the first day, and ever put it under the press again, not taking it therefrom, till the next day in the evening at soonest, and the last time it is turned, you shall turn it into the dry vat without any cloth at all.

When it is pressed sufficiently and taken from the vat, you shall then lay it in a kimnel, and rub it first on the one side, and then on the other with salt, and so let it lie all that night, then the next morning, you shall do the like again, and so turn it upon the brine, which comes from the salt two or three days or more, according to the bigness of the cheese, and then lay it upon a faire table or shelf to dry, forgetting not every day once to rub it all over with a clean cloth, and then to turn it, till such time that it be throughly dry, and fit to go into the cheese heck: and in this manner of drying you must observe to lay it first wh.re it may dry hastily, and after where it may dry at more leisure: thus may you make the best and most principal cheese. [1]

In short, you take your milk, scald it, add rennet (‘earning’), press it, and age it. The main difference that you see between this and modern home cheesemaking recipes, is that modern recipes call for the milk to be inoculated with a culture to cause the milk to acidify and curdle. Raw milk contains some bacteria, but the scalding process would kill some of it. The ‘earning,’ extracted from a calf’s stomach, would also have some cultures in it. (Markham also has instructions on how to prepare a rennet bag.)

So to simplify the process even more: take dairy, acidify it somehow, add a curdling agent such as rennet, extract the liquid, and … cheese.

The process I use for most of my cheesemaking is one which I have developed over the years to accomodate my schedule and lifestyle, and it is easily adapted to the current task.

Day 1, evening

The lactose-free milk arrived at my house, courtesy of my wife, who did the shopping that day. There were two liters of it, and they went into a clean bowl. To that I added a half cup or so of whey. Each time I make cheese, I save the whey. Sometimes I use it for cooking or other purposes, but the main reason I save it is for precisely this reason. I’ve been rolling the whey over for quite a few years now, so regardless of what the original starter that I used was, it’s now almost certainly developed its own character. In this, it’s similar to sourdough, which also develops its own microbiome if you use it long enough.

I then mixed a small squirt of vegetable rennet with a little cold water, and mixed that in with the milk.

Day 2, morning

The milk had set up nicely, so I cut the curds. I use a clean knife and cut it into a roughly 2 cm grid. Then I cut the curds horizontally. You can acquire special knives for this, with a right angle bend in them, but I just use a potato masher. I slide it in and level it off a couple of centimeters down, and move it back and forth to cut the curd.

Day 2, early evening

The cut curd had settled nicely by early evening, with a reasonable amount of whey already expressed from the curd.

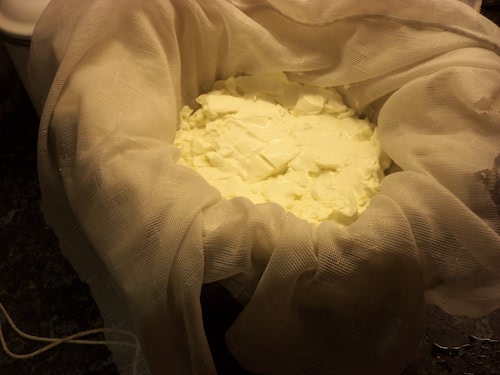

I put a colander into a pot and lined it with cheesecloth. Then I carefully slopped the curds and whey into the colander. You can see that the curds are still fairly wet and shiny and this point.

Day 2, late evening

A couple of hours later, the curds are looking quite a bit drier and firmer.

Which means it’s time to hang them!

Day 3, morning

After hanging overnight, the curds have drained and compressed into a single blob.

To the blob, I added perhaps half a teaspoon of salt. Then I broke up the curds a bit and mixed the salt in. If I was going to add herbs or something, this is the point I would do it, but I’m not so I didn’t.

Then it’s into the mold, and into the press with about seven pounds of weight. The weight itself is only about two pounds, but the lever arm on the press increases the pressure by roughly a factor of three.

Day 3, noonish

The weight is increased to about fifteen pounds.

Day 4, morning

The cheese is removed from the press, and the cheesecloth is removed from the cheese. It goes back in the press, upside down, just to smooth it out a little. The top is a little wrinkled from where the cloth was pressed into it.

Day 4, noonish

After five hours or so, it comes out of the press for the last time. At this point, the two liters of milk (which weighed roughly 2 kg) have turned into a cheese which weighs 333 gm.

I splashed it with some balsamic vinegar, because I felt like it, and placed it on a rack to dry. There’s a screen mesh cover which goes over it, too.

Day 12

The cheese had been aging for not quite two weeks. I cut it in half, to check on the progress and was satisified with the result. At this point, it was wrapped in parchment paper and moved to the fridge.

Day 27 or so

The final result was given to the Princess to use as she wishes.

Bibliography

Digby, Kenelm. The Closet of Sir Kenelm Digby Opened, edited by Stevenson, Jane, Peter Davidson. Devon: Prospect Books, 1997.

Markham, Gervase. The English Housewife, edited by Best, Michael R. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998.

[1] Markham, Gervase. The English Housewife, edited by Best, Michael R. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998.